Researchers decipher mechanisms of liver regeneration

23 May 2024

Scientists from the Berlin Institute of Health at Charité (BIH) and Open Targets together with colleagues from the University of Cambridge, and Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, UK, uncovered mechanisms driving regeneration of the liver during chronic liver disease. This regenerative process allows the liver to repair itself when chronically injured but could also result in progression toward cancer. The researchers were able to demonstrate this first by performing single-cell analyses on many biopsies obtained from patients with progressive Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). The results obtained in vivo were validated using cultured organoids in the laboratory. The scientists have now published their results in the journal Nature.

Ludovic Vallier grows mini livers, so-called organoids, to research how diseases of the liver develop and how they can be treated or prevented. He is Einstein professor for Stem Cells in Regenerative Therapies at the Berlin Institute of Health at Charité and Max-Planck-Fellow at Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics. As a long-term goal, he aims to use liver organoids for cell-based therapies for patients with liver failure.

Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) and its chronic form Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) are the leading cause of liver disease. It is estimated that 20-40% of the population have the benign form of the disease but around 115 million are currently affected by the chronic form. Despite recent progress, the only treatment for end stage MASH is liver transplantation, which involves heavy immune suppressive treatment while only a limited number of patients can benefit from this approach due to the lack of organ donor. Thus, Dr Chris Gribben and Dr Vasileios Galanakis from Vallier’s team as part of an Open Targets project, in collaboration with Dr Irina Mohorianu (Wellcome-MRC Cambridge Stem Cell Institute at the University of Cambridge) and Dr Michael Allison (Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust) turned their attention to researching this major health care challenge. “We were surprised to find that relatively little is known about the mechanisms occurring during the disease progression in humans. This is because studying a disease which can take decades to fully develop is very challenging. The technology necessary for extensive longitudinal studies became available only recently”, says Vallier.

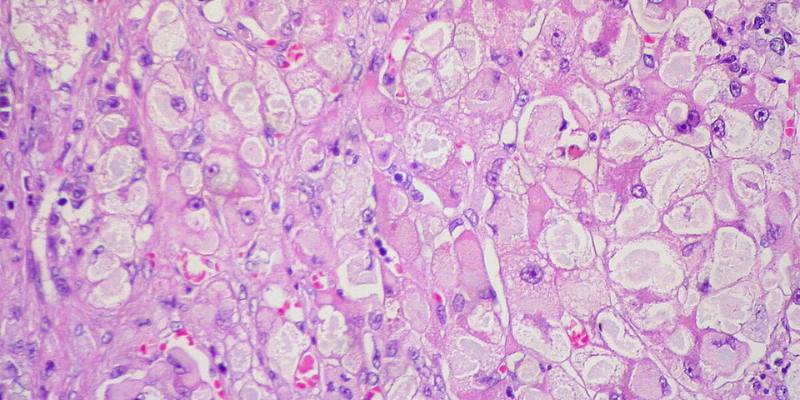

Chronic injury fundamentally changes the architecture of the liver.

The scientists collected small pieces of the liver (biopsy) from patients undergoing diagnostic tests in the MASLD service at Addenbrooke’s Hospital (Cambridge UK) and performed single-cell analyses to identify underlying mechanisms. These biopsies were collected from a large number of patients at different stages of the disease allowing for the first time to map MASLD progression in humans. They discovered an interesting mechanism: Chronic liver injury strongly damages the liver architecture especially the organization of the biliary tree, which represents a network of conduits draining the liver from toxins. This reorganisation is associated with a process of regeneration called transdifferentiation.

“We knew that disease progression could induce proliferation of cholangiocytes which are the main cell type composing the biliary tree. However, we did not expect this proliferation to be organized and to result in the production of such a complex network which strongly interferes with the architecture of the liver”, reports Vallier.

Disease progression is associated with signs of regeneration.

“Now, of course, we wanted to know whether this process was a sign that the liver is trying to repair itself or that the injury was progressing. For that, we performed detailed single-cell analyses and observed that cholangiocytes appear to transdifferentiate into hepatocytes, the main functional cell type of the liver. Thus, the organ tries desperately to replace the functional cells which are dying during the disease “, Vallier explains.

The exciting question was to uncover potential mechanisms behind this regenerative process: could we identify candidate factors which control regeneration? Vallier says: “We were very lucky to work in close collaboration with the Core Bioinformatics group led by Dr Irina Mohorianu. Together we could identify a list of factors which are up regulated during the transdifferentiation between cholangiocytes and hepatocytes. These factors were then validated in tissue collected from additional patients. Of particular interest, we found that Insulin signalling could play a major role thereby providing an interesting pathway for future therapeutic development.”

Principle also works in organoids grown in vitro…

In a next step, the scientists used cholangiocytes organoids derived from patients with progressive MASLD. These mini organs can be grown almost indefinitely in vitro while maintaining functions relevant for modelling disease. Of particular interest, the scientists show that cholangiocyte organoids can also transdifferentiate into hepatocyte-like-cells in vitro. This process could be blocked or promoted by respectively inhibiting or augmenting the insulin signaling pathway. Furthermore, additional factors identified in patients were present in vitro confirming the relevance of organoids to study regenerative mechanisms in a dish. “We were thus able to show that molecular mechanisms occurring in humans during a prolonged period of time can be studied in vitro,” says Ludovic Vallier. The results also suggested a more concerning aspect regarding organ regeneration.

…and these results could also be relevant for liver cancer

Indeed, most of the transdifferentiation events occur during the last phase of the disease when the liver is extremely damaged. Thus, this regenerative process is associated with disease progression and does not seem to be induced directly by injury. Furthermore, end stage liver diseases are strongly associated with liver cancer while several factors which seem to drive transdifferentiation in vivo and in vitro are also highly expressed in liver tumors. Thus, the scientists suspect that cancer could originate from regenerative processes gone bad. Indeed, chronic injury and diseased micro-environment could induce a large amount of stress on cells which would then become “plastic” and thus capable of transdifferentiating. However, this acquisition of plasticity could become abnormal if it goes too far.

The balance between regeneration and tumorigenesis is essential

This study shows that human organs can regenerate even after prolonged diseases and repetitive injury. However, this process is risky and can go wrong. Controlling cellular plasticity acquisition is crucial. These findings provoke a significant shift in our basic knowledge concerning the pathophysiology of chronic liver disease. This includes the discovery of new pathways that control the balance between disease progression vs. tissue repair and the identification of novel biomarkers for diagnostics and prognosis.

“We are of course excited by these results,” Ludovic Vallier reports, “because we believe we have found a way to develop new therapies which do not focus only on limiting disease progression but instead will aim to promote tissue repair. We know that we need more work before this knowledge has an impact on the clinic, but this is an essential first step. We can now focus on developing new therapies including cell-based approaches, which can ultimately help patients. And that is our goal!”

Publication

Gribben, C., Galanakis, V., Calderwood, A. et al. Acquisition of epithelial plasticity in human chronic liver disease. Nature (2024). doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07465-2

This press release was originally published by the Berlin Institutes of Health.

Image copyright ©Ed Uthman